Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia

Tinka's New Dress

Marionette theatre play, created and performed by Ronnie Burkett; premiered in 1994 at the Manitoba Theatre Centre. Since its creation, the work has toured extensively, notably to the Dublin Theatre Festival, the Public Theatre (New York), the Festival de Théâtre des Amériques (now Festival TransAmériques), London's Barbican Centre (1999), and the Melbourne International Arts Festival (2002). It has received multiple awards wherever it has been produced.

Tinka's New Dress is a fable based on the illegal underground "Daisy" plays of Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, with a cast of 30 characters. Burkett was inspired to write the play after reading about the history of Czech puppet theatre in Bil Baird’s The Art of the Puppet, in particular the account of the daring, illegal performances during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia – in homes and in basements. These plays were known as “Daisies” because they continued to bloom during a dark period, providing inspiration, information, and humour. Noted puppeteers and playwrights contributed anti-fascist scenarios for adults. Eventually all Czech puppetry was suppressed, and more than 100 skilled puppeteers and writers died under torture or in concentration camps.

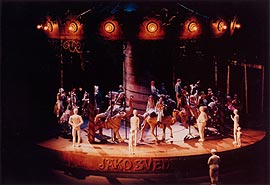

Tinka’s New Dress is set in “a vaguely European city and an internment camp on the outskirts” in the mid-20th century, although, as Burkett indicates in the published text, it is also “possibly the present or future” (i). The stage itself is configured as a faded Victorian-era carousel, on which the lives of the miniature actors turn. On the front curve of the stage decking are the words “As a Witness and a Warning.” Burkett’s marionettes enact the “real world” of puppet theatre in a totalitarian regime with the Orwellian name, “The Common Good,” performing the traditional “Franz and Schnitzel” comic folk play under the guidance of the elderly artisan, Stephan.

Stephan’s dissident apprentice puppeteer, Carl, and his sister Tinka, also frequent a dangerous underground cabaret named “The Penis Flytrap,” run by the drag-queen Morag, for whom Tinka creates extravagant costumes. Here, Carl’s satirical play-within-the play performances of the “Franz and Schnitzel” show comprise improvised satirical vaudeville specifically directed at Burkett’s contemporary audiences. Franz is a “grotesque psycho clown” and Schnitzel is “an elf-like child who longs to grow fairy wings” (i) and to fly. Their debates reference current political absurdities through bawdy and scatological jokes.

For Carl’s underground “Franz and Schnitzel” puppet shows, Burkett, as the character “Ronnie,” assumes the human portrayal of Carl, working on a small stage within the larger set, with a cast of characters “designed to look decidedly more puppet-like than the naturalistic marionettes in the dramatic body of the play” (i). Burkett’s physical presence in the performance gestures towards a political scenario in which individuals have lost personal freedom, and become “puppets” of the state – their strings pulled by an authority over which they have no control. This metatheatrical strategy also points to the role of the puppeteer as a satirist hiding behind his puppets: Schnitzel scrambles up the brocade curtains of his puppet theatre to see the face of his creator, and to protest against his helplessness: “Maybe I am but a vessel to be filled with another’s thoughts. May I’m being controlled from on high. Maybe I’m just a spokesperson for someone who’s too afraid to come down here and say these things himself. And if that’s the case, then sometimes I feel like looking up and screaming ... Why are you jerking me around like this? “(25)

Before the play begins, a soundtrack of the “Voice of the Common Good” warns citizens to have their identification cards available for inspection at all times, advising that “compliance is the core of civilization” (1), and urging citizens to report dissidents. This voiceover immediately establishes the political environment of a totalitarian government, into which audience members are now voluntarily entering. It could reference any number of countries and times: South Africa under apartheid, the former East Germany, Fascist Spain – or the present place at the present time. Once the house is in and the doors are closed, the Voice makes a final announcement: “This area is now secured. Movement will be monitored and discouraged” (1).

Carl asserts the importance of freedom of expression for an artist, but is cautioned by Stephan to be more circumspect in order to ensure that the performance can continue; and he disagrees with Carl’s ambition to use the theatre as a means to evade censorship and state control.

Carl finds a more sympathetic response in the person of Mrs. Astrid Van Craig, an educated and enlightened society woman who supports the arts. In his microcosm of society, Burkett places a variety of characters, who are sometimes capable of breaking through stereotypes, or of converting to opposite points of view. Even though his characters are carved in wood, they are still psychologically flexible. Mrs. Van Craig challenges Carl to develop and defend his embryonic views on the socio-political importance of art. She also praises his sister, Tinka’s artistry in the design of the marionette’s costumes.

Scene Two introduces the audience to “The Penis Flytrap,” an underground cabaret in which Carl performs his version of the “Franz and Schnitzel” show in his “Daisy Theatre.” The flamboyant transvestite host, Morag, provides a vehicle for anti-establishment jokes and sexual puns – a provocative response to the bigoted perceptions of a pervasively “straight” society, to which Burkett has a particular personal antipathy. Morag’s advice to Carl is: “And remember darling, make the bastards laugh. That way, they won’t know you said anything important until it’s too late” (15). In contrast, Carl’s risky venture is challenged by Fipsi, also an apprentice of Stephan, who believes that the “Franz and Schnitzel” show should be placed in the service of the state, not used as an instrument against it. She never improvises; she believes in following the script.

Scene Three comprises Carl’s “Franz and Schnitzel” show, as improvised by “Ronnie” playing Carl, “standing behind the gold curtain, visible from the chest up” (19) and manipulating both Franz and Schnitzel. The humour is grotesque – aimed at the audience, as well as the puppets, with jokes about wooden heads and incomprehensible performance art.

There are, however, evident political dynamics in the relationship between Franz and Schnitzel: Franz, the bully and boaster, occupies the right side of the stage, claiming that God is on his side; Schnitzel, the dreamer and idealist who wants to fly above life’s limitations like a “fairy,” (a retro reference to “gay”) occupies the left. Schnitzel struggles without much success to be independent of Franz and his base sexual preoccupations. Left alone with the audience, he voices his impossible desire for freedom.

His monologue is interrupted by the arrival of the Fat Lady, presaging the end of the play with her singing. Before she agrees to vacate the stage, she educates the audience into an appropriate response to her diva status. These direct addresses, typical of folk puppet theatre, build a close relationship with the audience, a community of believers which may be empowered for political agency. Theatre is, after all, a community-building process; hence it often becomes the target of censorship and subjected to closure under totalitarian regimes. When Franz returns to the stage, he announces that the original show has been cancelled, due to a radical change in audience and critical tastes. And so, there never is a “Franz and Schnitzel” show.”

In Scene Four, several club members respond to both Morag’s and Carl’s shows – demonstrating a wide range of tastes and inclinations, and the varying ways in which performance is received. It is most often misinterpreted and misunderstood. The critique of Carl’s performance by the critic, Hettie, is an ironic, self-reflexive comment by Ronnie Burkett on his own critical reception: “You had something to say, and you were hell bent to say it. And that’s fine. Don’t get me wrong. But say it through the puppets, kid. Make us believe in them so much that we forget it’s you” (43).

Inevitably, the number of performers in the underground cabaret is reduced as they are sent to the “Camp” or murdered, the implication being that artists are typically “outsiders” and “outcasts” in any society. Tinka and Carl continue to perform in the Camp, which tragically alludes to Thierenstadt, the concentration camp near Prague which the Nazis used as a showcase for interned artists. Carl is still compelled to perform, although his audience has dwindled; he has to discuss through his puppets the increasing erosion of rights and freedoms, even though now his life is at stake. Finally, his mentor, Stephan comes to the Camp to warn him stop his work; it is not worth dying for. Ronnie again associates himself with Carl by standing behind his puppet, “talking to the puppet and thinking Carl’s thoughts aloud” (76), while Carl hangs static, facing out: “Happy? You’re alone again. You like alone, you’re good at it. Fitting in, there’s the risk. Getting along, getting by, there’s the compromise. And compromise is ... death. Always so much death. But it never leads anywhere. I thought it was supposed to lead somewhere” (76-77).

By wearing the striped pyjama costume of the concentration camps, Ronnie aligns himself with those who suffered and died for artistic and political freedom, but he gives to Tinka a few words of hope, as she tells Carl that she has made a new dress, and is carrying Morag’s child – which is growing like a daisy in the darkness.

The second “Franz and Schnitzel” show provides some comic relief to this tragic scenario, but like the first, it never really happens. Schnitzel invites the Fat Lady to sing to bring his impossible performance to a close, but before his final exit he expresses his love for the audience, and his resolution to connect with them through thought and emotion. He would rather take his chances in the dark with the audience than stand in the light with Franz.

The final scene returns to Tinka in the Camp; Mrs Van Craig and then Stephan urge her to put on her new dress, and to continue her work in puppet theatre. Stephan finally asserts the importance of what they create: they have to keep the tradition alive. Ronnie again aligns himself with his marionettes by taking his place on stage in front of the backdrop, and whispers to Tinka in the voice of Carl. As the lights dim, he lifts his face upwards and whispers “fly.”

Burkett’s extraordinary marionettes challenge audience perceptions and response, and bring a world of wonders to a miniature stage. In the uncensored world of his theatre, anything is possible.

Tinka’s New Dress is published by River Books: Edmonton, 2002.

Commentary by Anne Nothof, Athabasca University.

Last updated 2011-02-15