Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia

Doc

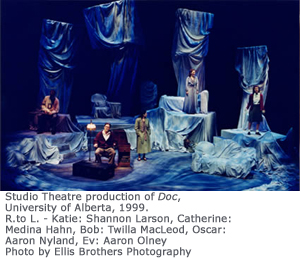

Play by Sharon Pollock, first produced in April 1984 at Theatre Calgary and in a revised version at Toronto Free Theatre in September 1984 (dir. Guy SprungTerry Gunvordahl, with music and sound score by Allan Rae.

Doc explores fraught domestic confrontations and evasions, and provides a harrowing look at the destructive emotional interior of a family from a double perspective of past and present through the memories of a father and a daughter. Ev and Catherine both re-enact the family history.

The play begins with the return of Catherine (a woman in her mid-30s) to the family home to visit her father (Doc Everett), who has suffered a heart attack. As in Pollock’s later plays Moving Pictures and End Dream, lives are re-experienced close to the moment of death. The confrontation of father and daughter resurrects ghosts from the past — Katie (Catherine as a child) and her dead mother, Bob. For Catherine this visit is inevitably an encounter with her mother, whose life with Ev was one of desperate loneliness and frustrated ambition, and ended with suicide. Ev’s own reliving of this relationship, however, provides a variorum to the text inscribed in Catherine’s memory. Her memories are not countered or rebutted, but are placed in juxtaposition to Doc’s: the “truth” remains occluded.

A family friend, Oscar, functions as intermediary and commentator, observing and interacting with his friend and colleague, Doc Everett, when he was a young, dedicated doctor and an insensitive husband and father.

Doc begins on a dark stage with insistent, overlapping whispers infiltrating the silence, anticipating “bits and pieces of dialogue heard later in the play” (Pollock’s program notes). A child’s rhyme, spoken by Katie, penetrates through the miasma of voices:

Fire on the mountain, kiss and run

On the mountain berries sweet

Pick as much as you can eat

By the berries’ bitter bark

Fire on the mountain break your heart

Years to come — kiss and run

Bitter bark — break your heart.

The rhyme anticipates the tragic family events and places the child’s perspective in relation to the others. In effect, it provides a choric comment on Catherine’s own history:

Stand up straight

Upon your feet

. . .

Choose the one you love so sweet

Now they’re married wish them well

First a girl, gee that’s swell

The woman, Catherine, is congruent with the child, Katie, and lives out the implications of the rhyme. Pollock often uses child’s verses or songs as echoes of the past, but also as ironic or tragic comments on the present – the “Lizzie Borden” verse in Blood Relations, for example.

As a young girl, Catherine has denied affinities with her mother, Bob, but as a woman she has come to empathize more with her, and Ev suggests that she is much like Bob. In her reassessment of the past, then, Catherine is indirectly assessing her own capacity for self-destruction as well as destructive behaviour in relationships. As a child she has seen “Gramma, and Mummy me . . .” in the mirror, and she doesn’t want to be like them.

The play ends with a reprise of Katie chanting the “Fire on the mountain” rhyme as her mother’s inevitable death draws closer. She blocks out the sound of Bob’s voice, and denies her a sympathetic audience, realizing too late that she never did hear her at all. As an adult, Catherine witnesses and re-experiences the anger, pain, and guilt of the child. However, in a ritualistic act of exorcism, she finally burns the letter written by Ev’s mother before she was killed by a train as she walked across a railway bridge – a letter that has haunted the family. Bob has insisted that this is a suicide note, in order to punish Ev with the responsibility for his mother’s death, but the contents are never revealed. As the letter burns, Catherine smiles at her father, an enigmatic acknowledgement of a shared understanding and acceptance, and a ritualistic purging of the past.

Although Doc is often read as a feminist play, showing the disintegration of a woman denied a means of personal fulfilment, it also shows the destructive consequences of an attitude that is wholly self-absorbed.

Commentary by Anne Nothof, Athabasca University

Last updated 2020-07-28