Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia

Joual

Quebec working-class dialect, pronounced "jwal" and derived from the French word cheval (horse).

The introduction of joual into the French-language plays of Gratien Gélinas and Michel Tremblay in the 1960s profoundly changed theatre in Canada. Joual was initially considered by some to be a horrific bastardization of French, but writers in Quebec have proven that any dialect can be rendered lyrical and expressive. Joual was finally accepted as one of the ways Quebec society expresses itself.

The prevalence of joual in Quebec working-class plays enabled the use of English dialects and vernacular in English-Canadian plays, bringing them more into a populist culture--from Michael Cook's and Codco's Newfoundland dialects to the Montreal anglo colloquial dialect of David Fennario's plays.

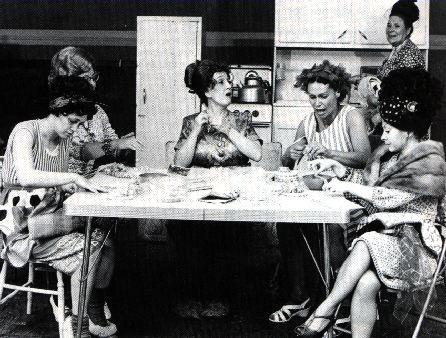

Perhaps the most historic (but certainly not the first) use of joual was in the Théâtre du Rideau Vert production of Michel Tremblay's Les Belles-soeurs, in which joual was not only presented as the natural idiom of the female working-class characters, but also composed in the form of quasi-musical oratorio (in the Bingo segment). From Michel Garneau's joual interpretations of Shakespeare to Jean Barbeau's joual fantasies (loaded with puns; even the titles!), joual has found a place in the theatre and is no longer greeted with the dismay, as when Les Belles-soeurs was refused a subsidy to travel abroad because of its joual. The language has been popularized world-wide through songs (notably of Robert Charlebois and Pauline Julien), poetry, film and television, although in France certain joual TV programs and films are subtitled.

It is important to note that joual is not simply a dialect, and it is often a political statement. In Tremblay's Hosanna, for instance, the transvestite's speech is as much in question as his sexual orientation. Is he Canadian? French? English? Québécois? The language provokes cultural and social debate.

The point of joual being a symbol of the Quebec class structure was brought home by Eloi de Grandmont's brilliant translation of Shaw's Pygmalion. In de Grandmont's work, the flower girl is enslaved by her joual (in the original, cockney), and needs to speak well to join polite society. The discussion of joual being a definition of Quebec poverty has been raised elsewhere, but rarely with such brio.

Where joual becomes problematic is in the translation of joual texts to English in Canada. John Van Burek and Bill Glassco, in their translations of the Tremblay works, skated around this by keeping many of the swearwords in French (joual uses religious swearing - tabarnac,ostie,câlice - unlike other French languages which use sexual cursing). A more fascinating approach was seen in a Scottish adaptation of Belles Soeurs called Guid Sisters which directly translated the working-class French into Scottish working class dialect. It worked beautifully and a production of Guid Sisters played in Montreal at Centaur Theatre in 1994 (where Les Belles-soeurs, which premiered in 1968, had never been performed before in English).

Commentary by Gaetan Charlebois

Last updated 2014-09-01