Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia

Alternative and Experimental Theatre

It could be argued that most, if not all, of Canadian theatre is alternative theatre: alternative to American or European theatre, alternative to anglo-Canadian theatre, alternative to "straight" theatre, etc. But for the purposes of this article, we will be discussing the theatre that was created in this country to advance theatre itself, to move it away from what was seen as "conservative," "traditional" or "reactionary." It must be noted, however, that much of this kind of theatre involved re-readings of the classics: many of the works at Montreal's Théâtre de La Veillée (Groupe [de] La Veillée, Espace de la Veillée) are deconstructions of Russian literature (i.e. Crime and Punishment); and Alexandre Marine's or Robert Lepage's works are reinterpretations of Shakespeare.

Although the 1960s are often seen as the time when home-grown alternative/experimental theatre was born, playwrights who were experimenting with form were writing and being performed well before then, notably Herman Voaden. Even before, though, works from the European and American alternative movements were finding audiences in Canada (Ionesco, Brecht, Beckett, etc.). Indeed, as far back as 1855, John Maddison Morton's enigmatic little farce Box and Cox was being performed by amateur societies across the country.

Although the founding of the Citadel Theatre (1965) hardly seems germane to this discussion, it is interesting to note that the first work of the company was Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, if only to suggest that certain works of the alternative movement were now being accepted by mainstream theatre.

George Luscombe's founding of Toronto Workshop Productions/TWP (1959), and Françoise Berd and Roland Laroche's formation of Théâtre de L'Égrégore, are seen as signs that alternative theatre was achieving a foothold in this country. TWP's and L'Égrégore's work shaped the Canadian alternative movement in two ways: both reinterpreted the classics and delighted in collective creation, which remain mainstays of alternative and experimental theatre to this day. By the time the next manifestation of the alternative movement occurred in the 1960s, a theatrical vocabulary had been established that new companies (like Theatre Passe Muraille, and Factory Theatre) and artists (like Michael Cook, Robert Gravel and Martin Kinch) could not ignore. Playwrights created works for virtually any kind of space: from church basements to churchyards, beneath turnpikes, on wharves, and in warehouses. Many alternative companies (like Toronto Free Theatre) were also run by hybrid artists (actors/writers/directors/producers) who continue to dominate alternative and experimental theatre: Jean-Frédéric Messier and Dominic Champagne, for instance. This is a Canadian theatre reality, however, as it is still very difficult to earn a living as a specialist. And theatre has increasingly become a "crossover" form -- a performance art incorporating movement, dance, music, and projections.

With the end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s, alternative and experimental theatre in Canada became considerably more transgressive in nature, challenging social and gender "norms" and assumptions. Feminist Theatre and Gay and Lesbian Theatre, for example, have been iconoclastic in both form and content. Alternative theatre has typically been politically charged, and satiric in style: the element of risk (arguably central to the definition of the genre) was broadened. Michael Hollingsworth, for example, cleverly satirizes the political history of Canada in his VideoCabaret series.

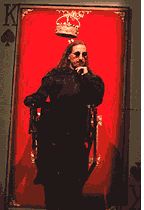

Trudeau and the FLQ, with John Dolan

(foreground), 1996.

Alternative theatre has undertaken previously unexplored and more controversial territory, like sexual deviance. (Ken Gass's Winter Offensive was hotly debated in Toronto in 1978). It has also incorporated startling and sometimes obscure imagery (like the hanging piano in Robert Lepage's Tectonic Plates, for example). Fusionist works (arguably posited by Voaden), which blended several forms were given labels that came and went (sometimes very quickly): happenings, performance art, spoken word. What might have been considered alternative or experimental in the 1960s (like the disturbing works of Judith Thompson or the "Marxist" works of David Fennario), have now entered the mainstream houses such as Tarragon Theatre and Centaur Theatre, although even there, occasionally, they caused a stir like Denise Boucher's highly controversial Les fées ont soif, performed at the mainstream Théâtre du Nouveau Monde.

But almost from the beginnings of alternative theatre in Canada, the lines between it and the mainstream have been blurry, especially with the creation of the Local Initiatives Program (LIP, 1971), which gave grants to a wide variety of theatres, many flash-in-the-pan, as an attempt towards lowering the unemployment rate. Many of the "alternative" companies which used the LIP grants (like Open Circle Theatre) as a way to get around the more restrictive arts funding eligibility requirements also flirted with the mainstream and some, like Alberta Theatre Projects, have become more mainstream than alternative.

The line continues to blur as artists who started out as alternative are helming mainstream companies. One example is Lorraine Pintal, who has brought a spirit of exploration to Théâtre du Nouveau Monde.

However, there are still dozens of small companies across the country, many underfunded, which celebrate exploration and experimentation in theatre (Theatre Yes, The Other Theatre, MT Space, One Yellow Rabbit, Rumble Theatre, and many more are formed every year by graduates of theatre programs. Some are formed for performances at the Fringe Movement across the country, or to address specific social issues; for example, Headlines Theatre.

Commentary by Gaetan Charlebois and Anne Nothof

Last updated 2019-11-19